Ebook Info

- Published: 2014

- Number of pages: 336 pages

- Format: PDF

- File Size: 1.51 MB

- Authors: Derek Bickerton

Description

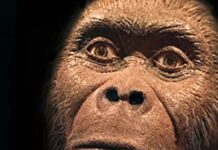

The human mind is an unlikely evolutionary adaptation. How did humans acquire cognitive capacities far more powerful than anything a hunting-and-gathering primate needed to survive? Alfred Russel Wallace, co-founder with Darwin of evolutionary theory, saw humans as “divine exceptions” to natural selection. Darwin thought use of language might have shaped our sophisticated brains, but his hypothesis remained an intriguing guess–until now. Combining state-of-the-art research with forty years of writing and thinking about language evolution, Derek Bickerton convincingly resolves a crucial problem that both biology and the cognitive sciences have hitherto ignored or evaded.What evolved first was neither language nor intelligence–merely normal animal communication plus displacement. That was enough to break restrictions on both thought and communication that bound all other animals. The brain self-organized to store and automatically process its new input, words. But words, which are inextricably linked to the concepts they represent, had to be accessible to consciousness. The inevitable consequence was a cognitive engine able to voluntarily merge both thoughts and words into meaningful combinations. Only in a third phase could language emerge, as humans began to tinker with a medium that, when used for communication, was adequate for speakers but suboptimal for hearers.Starting from humankind’s remotest past, More than Nature Needs transcends nativist thesis and empiricist antithesis by presenting a revolutionary synthesis–one that instead of merely repeating “nature and nurture” clichés shows specifically and in a principled manner how and why the synthesis came about.

User’s Reviews

Editorial Reviews: Review “Bickerton is the grand seigneur of the topic of language evolution among the linguists. He writes so bloody well that one turns green with envy. He is a mastermind of the field, period.”―Eörs Szathmáry, Professor of Biology in the Department of Plant Taxonomy & Ecology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest“More than Nature Needs is terrific, provocative, controversial, up-to-date, and written with a refreshing take-no-prisoners attitude. Theories of the evolution of language are notoriously hard to test, but Bickerton’s, which embeds a serious critique of contemporary linguistics, is well worthy of serious consideration. A top-notch effort by a leader in the field, in the middle of his ninth decade.”―Gary Marcus, Professor of Psychology and Director of the Center for Language and Music at New York University“Wide-ranging…A novel inquiry into the evolution of language…Deeply thought-provoking…Highly stimulating.”―Stephen Levinson, Science About the Author Derek Bickerton (1926–2018) was Professor Emeritus of Linguistics at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Reviews from Amazon users which were colected at the time this book was published on the website:

⭐I’ve been a fan of Derek Bickerton’s writing and thinking on linguistics since happening upon Language and Species in a Philadelphia bookstore, disturbingly many decades ago. More Than Nature Needs, the latest addition to Bickerton’s canon, is an intriguing and worthy one, and IMO is considerably deeper than its predecessor Adam’s Tongue.Adam’s Tongue argues that the elements of human symbolic language likely emerged via scavenging behavior, as this was an early case in which early humans would have needed to systematically refer to situations not within the common physical enviroment of the speaker and hearer. This is an interesting speculation, showcasing Bickerton’s inventiveness as a lateral thinker. MTNN continues in this vein, exploring the ways in which language may have emerged from simplistic proto-language. However, MTNN draws more extensively on Bickerton’s expertise as a linguist, and hence ends up being more profoundly thought-provoking and incisive.As I see it, the core point of MTNN — rephrased into my own terminology somewhat — is that the developmental trajectory from proto-language to fully grammatical, proper language should be viewed as a combination of natural-selection and cultural/psychological self-organization. To simplify a bit: Natural selection gave humans the core of language, the abstract “universal grammar” (UG) which underlies all human languages and is in some way wired into the brain; whereas cultural/psychological self-organization took us the rest of the way from universal grammar to actual specific languages.The early stages of the book spend a bunch of time arguing against a purely learning-oriented view of language organization, stressing the case that some sort of innate, evolved universal grammar capability does exist. But the UG Bickerton favors is a long way from classic-Chomskian Principles and Parameters — it is more of an abstract set of word-organization patterns, which requires lots of individual and cultural creativity to get turned into a language.I suspect the view he presents is basically correct. I am not sure it’s quite as novel as the author proposes; a review in Biolinguistics cites some literature where others present similar perspectives. In a broader sense, the mix of selection-based and self-organization-based ideas reminded me of the good old cognitive science book Rethinking Innateness (and lots of other stuff written in that same vein since). However, Bickerton presents his ideas far more accessibly and entertainingly than the typical academic paper, and provides interesting stories and specifics going along with the abstractions.He also bolsters his perspective via relating it to the study of creoles and pidgins, an area in which he has done extensive linguistics research over many decades. He presents an intriguing argument that children can create a creole (a true language) in a single generation, building on the pidgins used by their parents and the other adults around them. I can’t assess this aspect of his argument carefully, as I’m not much of a creologist (creologian??), but it’s fascinating to read. There is ingenuity in the general approach of investigating creole language formation as a set of examples of recent-past language creation.The specific linguistics examples in the book are given in a variant of Chomskian linguistics (i.e. generative grammar), in which a deep and surface structure are distinguished, and it’s assumed that grammar involves “moving” of words from their positions in the deep structure to their new positions in the surface structure. Here I tend to differ from Bickerton. Ray Jackendoff and others have made heroic efforts to modernize generative grammar and connect it with cognitive science and neuroscience, but in the end, I’m still not convinced it’s a great paradigm for linguistic analysis. I much more favor Dick Hudson’s Word Grammar approach to grammatical formalization (which will not be surprising to anyone familiar with my work, as Word Grammar’s theory of cognitive linguistics is similar to aspects of the OpenCog AGI architecture that I am now helping develop; and Word Grammar is fairly similar to the link grammar that is currently used within OpenCog).Word Grammar also has a deep vs. surface structure dichotomy – but the deep structure is a sort of semantic graph. In a Word Grammar version of the core hypothesis of MTNN, the evolved UG would be a semantic graph framework for organizing words and concepts, plus a few basic constraints for linearizing graphs into series of words (e.g. landmark transitivity, for the 3 Word Grammar geeks reading this). But the lexicon, along with various other particular linearization constraints dealing with odd cases, would emerge culturally and be learned by individuals.(If I were rich and had more free time, I’d organize some sort of linguistics pow-wow on one of my private islands, and invite Bickerton and Hudson to brainstorm together with me for a few weeks; as I really think Word Grammar would suit Bickerton’s psycholinguistic perspective much better than the quasi-Chomskian approach he now favors.)But anyhow, stepping back from deep-dive scientific quibbles: I think MTNN is very well worth reading for anyone interested in language and its evolution. Some of the technical bits will be slow going for readers unfamiliar with technical linguistics — but this is only a small percentage of the book, and most of it reads very smoothly and entertainingly in the classic Derek Bickerton style. Soo … highly recommended!

⭐This book was written to attempt an answer to a problem, Wallace’s problem, that has long bedeviled those who study evolution. Why are human brains and language so much different and more complex than would seem necessary? How could this leap, this gap, occur?Derek Bickerton has outlined the most likely scenario yet for the development of language, probably beginning with Homo erectus. He combines common sense with developmental data and evidence, drawing parallels and noting differences between the human origin of language and language acquisition in infants today, the development of creoles from pidgins, and work with the great apes using symbols, to cross that seemingly insurmountable gap in three smaller steps, not one large leap.First would have had to come the protowords of the lexicon. This makes logical sense. You can’t have syntax without a lexicon, the words. Then, perhaps much later, the attachment of these words to each other in short, two-word phrases, a protolanguage, with the emergence of “telegraphic speech”. Finally, in fits and starts, after a long period of brain reorganization, the phrases and clauses of full-blown syntax developed. Bickerton sees this attachment and organization into phrases and clauses as a type of Universal Grammar, although one much different and less specified than pictured by Chomsky. I personally lean toward the idea, as put forth by Daniel Everett and others, that learning is sufficient to explain childhood language acquisition, granted the more efficient economy and automatization of modern human brains.Bickerton saw language as being primarily a system of representation. (See Language and Species.)Communication is what that system does, but a system of representation is what it is. And as in any significant new source of information or representation (like those of the senses) the brain went through a long period of wiring reorganization and automaticity to make its work of connecting, first, protowords to concepts, and then those concepts to each other, easier and faster.Bickerton posits that the significant departure from other animal communication came with displacement, or offline thinking. When combined with fully-developed syntax, this hypothesis explains much, including our expanded ability to mentally travel in time and make plans. Offline thinking would have been necessary for the gradual expansion of our special type of human self-consciousness as well as imagination, recursive thinking, and artistic and other forms of representation.Although the evidence is sparse and inconclusive, this hypothesis fits what evidence we have better than any other. It is parsimonious and elegant while explaining and retaining the phenomena. Research into child language acquisition, ape symbol use, and the development of creoles from pidgin offer some support for Bickerton’s position. Protolanguage (or merely early language, as preferred by Everett) would have given Homo erectus conceptual ability for both limited tool use and navigation at sea, while the much later complete syntax would account for the lack of evidence for more advanced representational thinking and artifacts until circa 50,000 to 100,000 years ago.This theory of the development of language contains elements of both invention and innateness. The advent of protowords would have been an invention, Bickerton posits, to aid in cooperative scavenging. The rewiring of the brain for economy and ease in handling this new source of information introduced an innate element, although the topic of innateness is highly controversial. Finally, as full-blown language developed, culture took over to produce the variety of diversity in language we see today.Is this science? I think it undoubtedly is. Science is sometimes taking the evidence we have and making our best hypotheses. Perhaps the most speculative part of this theory is language’s origin in cooperative scavenging, but it is a likely scenario. Although fire could have been the catalyst, or possibly monogamous pair bonding, or something else entirely. Improved information retrieval methods may someday tell us more.Derek Bickerton passed away this year, at the age of 91. I didn’t have the honor of knowing him personally, but I can vividly imagine the sense of satisfaction and fulfillment he must have felt after crowning a lifetime of linguistic study and scholarship with the completion of More than Nature Needs.

⭐After two readings of More than Nature Needs, I can state without qualification that my pleasure in it has been immense. I particularly value Derek Bickerton’s incorporating a range of relevant fields from paleontology, developmental biology, ecology, animal behavior , as well as language and linguistics into a more cohesive, coherent and structured argument for the origin of language. His careful presentation of evidence for, as well as objections to, his proposals evidence a sound awareness of the tentativeness of all scientific endeavor-in-process. The book is incisively written and argued with exquisite attention to crucial details in language origin and development. William of Ockham is surely smiling down on this fine work.

⭐An in-depth look at a complex subject. Written for the advanced lay person but capable of being entertaining even if you follow one of the fields it touches on.I liked this so much I gave two out as gifts.

⭐The book would be much more readable if references were left for the end; instead, the book is littered with parenthetical wording, lowering the readability. Also, the author spends way too much time discrediting other studies while not spending enough time on the things that prove the title of his book. There are a few tidbits of useful information, including proto languages, but this is just not an enjoyable (or useful) read.

⭐Prompt shipping. I appreciate it.

⭐Very instructive read. Jim.

Keywords

Free Download More than Nature Needs: Language, Mind, and Evolution in PDF format

More than Nature Needs: Language, Mind, and Evolution PDF Free Download

Download More than Nature Needs: Language, Mind, and Evolution 2014 PDF Free

More than Nature Needs: Language, Mind, and Evolution 2014 PDF Free Download

Download More than Nature Needs: Language, Mind, and Evolution PDF

Free Download Ebook More than Nature Needs: Language, Mind, and Evolution