Ebook Info

- Published: 2006

- Number of pages: 248 pages

- Format: PDF

- File Size: 0.72 MB

- Authors: David Markson

Description

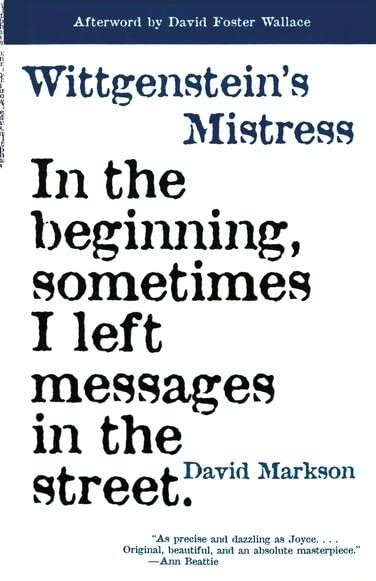

Wittgenstein’s Mistress is a novel unlike anything David Markson or anyone else has ever written before. It is the story of a woman who is convinced and, astonishingly, will ultimately convince the reader as well that she is the only person left on earth.Presumably she is mad. And yet so appealing is her character, and so witty and seductive her narrative voice, that we will follow her hypnotically as she unloads the intellectual baggage of a lifetime in a series of irreverent meditations on everything and everybody from Brahms to sex to Heidegger to Helen of Troy. And as she contemplates aspects of the troubled past which have brought her to her present state―obviously a metaphor for ultimate loneliness―so too will her drama become one of the few certifiably original fictions of our time.“The novel I liked best this year,” said the Washington Times upon the book’s publication; “one dizzying, delightful, funny passage after another . . . Wittgenstein’s Mistress gives proof positive that the experimental novel can produce high, pure works of imagination.”

User’s Reviews

Editorial Reviews: Review “Beautifully conceived. An irresistible, captivating book!” (Walter Abish)“Beautifully realized. Initially as hypnotically calming as an afternoon snowfall, then, by stages as menacing and yet thrilling as a nocturnal blizzard. This is Markson in the post-Beckett Gaddis country, staking his own claim, in a territory nobody else has the courage or the strength to inhabit and survive in.” (James McCourt)“Provocative, learned, wacko, brilliant, and extravagantly comic. This is a nonesuch novel, a formidable work of art by a writer who kicks tradition out the window, then kicks the window out the window, letting a splendid new light into the room.” (William Kennedy)“Unsettling, shimmering . . . compelling.” (Publishers Weekly)“A work of genius . . . an erudite, breathtakingly cerebral novel whose prose is crystal and whose voice rivets and whose conclusion defies you not to cry.” (David Foster Wallace)“Brilliant and often hilarious . . . Markson is one working novelist I can think of who can claim affinities with Joyce, Gaddis, and Lowry, no less than with Beckett.” (San Francisco Review of Books)“Addresses formidable philosophic questions with tremendous wit . . . remarkable . . . a novel that can be parsed like a sentence; it is that well made.” (The New York Times Book Review) About the Author David Markson’s novel Wittgenstein’s Mistress was acclaimed by David Foster Wallace as “pretty much the high point of experimental fiction in this country.” His other novels, including Reader’s Block, Springer’s Progress, and Vanishing Point, have expanded this high reputation. His novel The Ballad of Dingus Magee was made into the film Dirty Dingus Magee, which starred Frank Sinatra, and he is also the author of three crime novels. Born in Albany, New York, he lived in New York City until his death in 2010.Stephen Moore is an American author and literary critic.

Reviews from Amazon users which were colected at the time this book was published on the website:

⭐Ludwig Wittgenstein, an Austrian born philosopher and Cambridge professor (1889-1951): “Was convinced that language creates a picture of the real world and that most philosophical problems are merely the result of philosophers’ misuse of language; experience only seems complicated because of our confused descriptions of it, which represent knots in our understanding. Untangle the knots and, according to the theory, philosophical questions will simply dissolve. [p. 326. An Incomplete Education. (1987) Judy Jones & William Wilson.]It seems to me David Markson’s novel Wittgenstein’s Mistress (1988) is an attempt to untangle Wittgenstein’s philosophy as laid down in his book (Wittgenstein’s) Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, via the workings of the mind of a mid-aged woman, Kate, left alone in the world – all alone. Her mind’s workings, or “inconsequential perplexities” (= anxiety); is the subject matter of the story. There is not really a plot in the conventional sense. Kate puzzles over (among many other things) a book she found in a carton of books, in the basement of a house she’s taken to living in, on the beach of the northeast coast of Italy, sometime in modern times because there are cars and trucks for the taking and driving and playing of music in tape decks (electricity and all power energy is defunct.) There are tennis balls, rackets, and a court. Perhaps a domestic cat has survived with her. She remembers, if not always accurately, the history of writing, philosophy, art, and music. The book she puzzles over is titled Baseball When the Grass Was Green (a real book) which throws her for a loop, or ties her mind in knots. Kate thinks that the book ought to have been called, “baseball when the grass IS real,” and then decides “baseball when the grass is growing,” would be better still. (p 95) Subsequently, she finds another carton that contains some artificial turf (fake grass) and that then further confounds her – she apparently having no known or actual experience of baseball, calling Stan Musial (Of whom there is a huge bronze statue of out in front of Busch Stadium in St. Louis. Really.) “Sam Usual,” and later “Stan Usual.” And also, she calls Lou Gehrig, “Stan Gehrig.” In fact, she even mixes up her dead son, Simon, with her dead lover, Lucien, and can’t remember if her dead husband, Adam, started drinking to excess because she had had lovers, or she took to taking lovers because he drank to the degree of being drunk. And then of course – What does any of anything matter anyway if no one is around to talk to, or with, to argue with or against, except only the voices and/or recollections of what you remember, or have read, and what did the writers’ of books know anyway – of what was real and what was not real – what with words only to explain what was observed. What is real grass anyway: “I [Kate] imagine what I mean is that if the grass that is not real is real, as it undoubtedly is, what would be the difference between the way grass that is not real is real and the way real grass is real, then?” (p 193)Well that question hardly seems worth one’s time considering, in that it is an “inconsequential perplexity.” Which is sort of the point, here. Is she mad (crazy) or not. She can’t quite remember if it was Heidegger, who she HAD corresponded with, or Nietzsche, or Kierkegaard who had wrote about inconsequential perplexities. (p 216-7) And that anxiety was the default, or “fundamental” mood of humans. And so on and so forth.So the question is as it always is: Should YOU read this book? I say yes. If. …There are three populations of people who I think would enjoy this read. Picture a Venn diagram of three circles (=categories of people.) One circle would be persons formally educated in Philosophy, Art, and/or Literature, to include persons who have read and enjoyed reading David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. I say this because there is a great deal of references to philosophy and thinking, art and artists, and literature and writers. I say DFW and Infinite Jest (1996) specifically because you can see how Markson’s book gave permission to Wallace to do what he did within the pages of IJ. Moreover, there is the exploration of, or untangling of, or application of thinking, of mine and perhaps yours, and of the thinking of Ludwig Wittgenstein, in both WM and IJ – both writers’ book’s playing with the concept of words and language and how they shape thought, which then impacts a person’s subjective reality. Both writers explore, in great detail, the idea that language is, as commonly used, very imprecise. There is the idea of reading/using footnotes, in both books. There is a great deal of redundancy and repetition of words, sentences, and ideas, in both books. There are hundreds and hundreds of characters, in both books, albeit in WM they are mostly historical characters and in IJ they are fictional. And the whole idea of thinking itself. Kate imagines that these hard thinking men, like Ludwig Wittgenstein, you can actually observe, see them, thinking – that there is an observable difference between a person who is thinking hard, and a person who is hardly thinking. I’m thinking that thought, expressed by Kate, was in fact integrated into Wallace’s being, his Self, as you can certainly see Wallace thinking, observe his mind working, if you watch him converse with interviewers on YouTube. There is the technique of the author being aware of what he is doing, and mocking himself and what he is doing in the text via the thinking of a character/narrator. “Am I just showing off?” Kate asks of herself several times, speaking to the reader, who she hopes may read what she is writing, someday. There is the concept of being alone, loneliness, anxiety, sadness, and depression. There is tennis. There is the idea of where does a thought originate and how do we learn. Which brings me to a problem I had with the book: How much of it is true. I believe that in fiction, all the little things should be true, so as to get the reader to buy into the big lie – which is, of course, the fiction itself, the story. In WM, Markson, via Kate, asserts that Michelangelo said something like, “There is no better way of being sane and free from anxiety than by being mad.” (p 192) When I read that, which is repeated in the text several times, I thought —I have heard or had that thought before … and then it came to me: It was in a song written by Waylon Jennings in the 1980s, I’ve Always Been Crazy. The lyric is: “I’ve always been crazy but it kept me from going insane.” Which might, or perhaps not, have been intentional by Markson – the confusion. I have no idea about what he, Markson, was thinking.A second circle, or population, would be persons who are overly anxious, or score high on neurotic indices, to include creatives and artists (= writers, painters, thinkers, etc.) for obvious reasons. Most people like to read about others like themselves, to know that they are not alone, that there are other people on the planet with similar attributes [In this case anxiety(s).] Thus one might think, Maybe I’m NOT so crazy after all.The third and last circle of the diagram would be persons who have experienced, or are curious about, what it is to be all alone for a long period of time, such as solo wilderness hikers, solo sailors, fire lookouts back-in-the-day, or the sole survivor, of something or another, on planet earth. The ideal reader would be a person who fits into the section of the Venn diagram where all three circles intersect. I’m close, and so I loved this book! I highly recommend it to you if you think you fit into, or are curious about, any of the three populations. It is unconventional, experimental, and like Infinite Jest, the plot is almost irrelevant, though this novel is way, way, shorter, 240 pages. [I did not read the afterword, The Empty Plenum, (1990) 32 pages, by David Foster Wallace, before writing this review.] It is a quick read, and fun. You need not be familiar with all the historical references to get it, is my thinking.

⭐This is one of those books that can not and should not be written again, but in a good way. There. That’s the weird part. Basically, I’m into odd literature (probably got suggested this since the algorithm saw Infinite Jest in the history) and this is really unlike anything I’ve read before. So you have your narrator, typing away as the last woman on earth (the blurb on the back of the book makes it ambiguous but it’s more fun to just accept it as the truth), letting out her thoughts, the things that have come from years of solitude, on paper, paper being about the closest thing to someone listening that she can get. I guess the only thing I can say about it is…you get how she’s been alone with her thoughts for so long. You get the whole feeling of the internal world she’s created out of the shards of the world that used to be, or at least what she thinks she has preserved of it, and it all feels very human and personal throughout. Relatable, even, if you can honestly think about what you’d do in that situation. There are tons of references in there, yes, but no, you don’t have to know them. Sure, there are definitely layers going on here, as the essay by David Foster Wallace talks about, but you don’t need to know all of the references or even that many of them. It stands on its own without knowing much as long as you’re willing to keep reading and learn from what she says. Though there is a lot of thinking if you want to take a reading to its final conclusion- as in the aforementioned essay at the end of the book- you can also get a lot out of this with just feeling. I’ll stop at the “feeling and reading the essay at the end” level and be very happy with it.

⭐After getting through 1/3 of the book or so, I have decided that holding this book in my conscious experience gives me psychic damage. That’s not to say the book or its themes are “bad”, but the depiction of loneliness, madness, and an ab-initio human experience (?) feel like they rub off. This book does make me so grateful for human connection and my friends and having a normal time in my life. But I strongly dislike the psychological inertia that this book holds in my thoughts after I put it down… I will pick this book back up when my will is stronger, and perhaps ingest it in smaller doses.

⭐This book gave me a headache. An intellectual rant of no consequence. The copy I received had some lines of print dropped one font size, (to make it fit on the page? That gives away a formatting error the publisher couldn’t deal with) or maybe that was part of the experimental part of the novel where I maybe zoned out. Finishing it was agony.

⭐I absolutely loved this book. It was funny and also desperately sad. The way the narrator’s character is brought to life through the writing is just great. I can’t believe that a man wrote this from the perspective of a woman.

⭐Wow, this was amazing. Totally mind-blowing. An earth-shattering masterpiece.

⭐True Germ

⭐It’s rare I don’t finish a book I start. But it does happen. This book is drivel. A sequence of scrambled sentences, about ten or so topics, continuing for however many pages. If you read it all you might indeed find yourself in an altered state. And perhaps it does qualify as *art*. But it is definitely not a good book.

Keywords

Free Download Wittgenstein’s Mistress in PDF format

Wittgenstein’s Mistress PDF Free Download

Download Wittgenstein’s Mistress 2006 PDF Free

Wittgenstein’s Mistress 2006 PDF Free Download

Download Wittgenstein’s Mistress PDF

Free Download Ebook Wittgenstein’s Mistress